About Urbanism

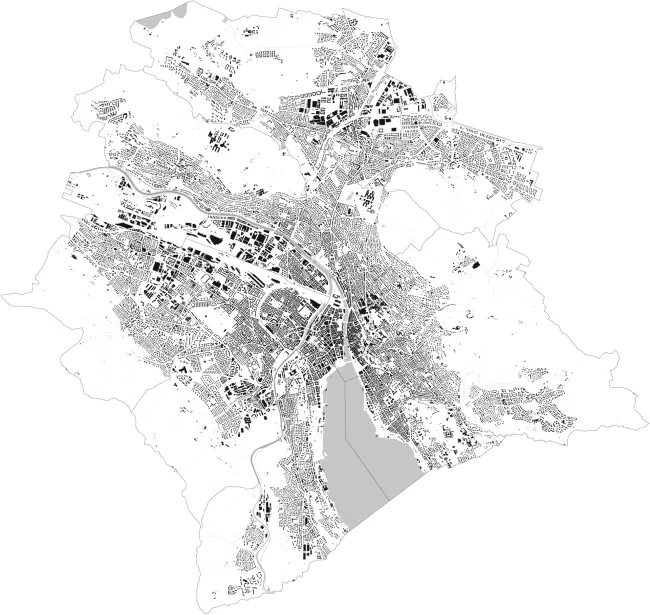

Zurich Figure Ground Plan

Urbanism is one of Switzerland’s tricky pet projects. With the rhythm of a pendulum, one follows the expansion trends from the city center to the agglomeration. It is a long history of collapse that began successfully and confidently. Thinking back to the early 20th century and how the beginning of broadly applied city expansions initiated metropolitan development, one recognizes the incredible current relevance. The intent to merge Zurich with its suburbs, to design a morphological “Greater Zurich,” and thus to allow the expanded city territory a new form that will be regarded on political and infrastructural levels as having a new scale, is unimaginable today despite the obvious necessity. Here it is noteworthy, that in the span of approximately one-hundred years, a diametrically different political culture unfolded.

While at that time a spirit of entrepreneurship, shaped by a few extraordinary personalities dominated politics, today architects stand lost in the forums held by community organizations.

Zurich City View, 2025

© E2AThat today the once decisive, politically active Zurich entrepreneurs have been replaced by broadly distributed participation of the populace does not mean that the city can afford to operate without a dominant and communicative political position, especially because a failure lacking a clear initial position has become politically acceptable and tolerable to all. Thus, we are characterized by pro forma politics that act not only on the global, but also on the local scale and so markedly delays previously declared positions or mutually agreed-upon goals that in a potential collapse neither the goal itself nor the leaders can be held responsible.

In the 1920s, as Daniel Burnham was formulating his spirit of “Make no little plans” with the expansion for Chicago, he happened upon a time in which from America, to Berlin, and to Zurich, the development tendencies were politically pushed to be conceived on a grand scale and, equally impressive, were successfully passed when set before the general population for the determining vote.

The plan was definitely not an undemocratic process, but instead reflected a political change that recognized the relevance of considering the city systematically and as large-scaled in response to intensely increasing activity.

Karl Moser’s 1933 plan to clean up the district of Niederdorf1 reveals ambitions to reassess Zurich’s central city concept, especially because over the period of many years, he was directly commissioned by the city council to develop realistic alternatives for the city center in various scales. While in the ‘30s Moser still believed in the reconstruction of the center and was heavily influenced by the precedent of Le Corbusier’s Tabula Rasa plan for Paris, the post-war years saw increasing frustration over abandoned desires for reconstruction of the city center. In the form of antithetic development, the city and the country-side became increasingly polarized.The eloquently encouraged change of direction at the end of the 1950s heralded the turning away from the growing city and formulated functionally separated and compositionally organized development as a requirement of the modern city. While high-rises were banned from the fought-over city by reactionary forces, they were built in the still-open fields of the future agglomeration. With a few exceptions such as André Bosshards City in the Water2, only in the ‘70s did planners once again regain the confidence to return to the city. Methodically and with similar compositional approaches, they ventured into Zurich’s den of lions.

The proposed Lake Park by Werner Müller3 solved not only the problem of parking places in the inner city, but also foresaw the potential in crossing the lake, a possibility which would only much later be recognized as desirable. A plan developed in 1971 by Guhl, Lechner, and Philipp for 150,000 inhabitants, an approximately four kilometer long residential city on the railway tracks, envisioned not only a radical, linear city in the middle of the existing, but also precisely addressed the present-day masses of commuters displaced daily from the city.4 In fact, their proposal already addressed today’s constant calls for more residential space much more than the later projects of HB Southwest and Eurogate.5 And this was without degenerating into the schematic scale of a megastructure. While the return to the growing city was linked to the authorship of the proposals, since the early 1960s, the ongoing development of settlement compositions outside of the territorially defined city were architecturally and urbanistically “anonymous.” Though the architectural history from the ‘50s has been very well researched and analyzed, the time period from the ‘60s until the early ‘70s has been swept under the carpet.

Urban View toward the Alps, 2025

© E2AThe designers disappeared into oblivion amidst the emerging critique of ghettoization and a theoretically latent disinterest in urbanism. To some extent, having been blinded by early enthusiasm, they were embarrassed to recognize the increasing difficulties of effectively realizing developments and mass-residential buildings in attempts toward modern city expansion. Then who designed Spreitenbach or Dietikon?6

With the introduction of the spatial planning laws, the 1980s blocked the expansion ideas of the city as one would have hoped for the agglomeration. From this legal basis a new profession was created: the urban planner.As custodians of developments and recreational spaces, the urban planner entered into the field of urbanity, often in opposition to the architects who had become silent on the issue. As such, the architects concentrated on architecture without having to risk the reaction of the city.The insistence on the defined and predetermined aesthetic of the city based on the existing, which dominated the political mood until the mid-‘90s, documented the deteriorating independent discourse about urban expansion. That today, almost 30 years later, one must for once recognize that urban planning as the goal of spatial housekeeping has been anything other than achieved, is not surprising in the context of all previous attempts. Despite regulation, the suburban space of the agglomeration has exploded. Exactly that, which one would want to legally secure has been definitively lost.Today, as before, more than 60% of all new buildings in Switzerland are constructed in communities of less than 10,000 residents. The communities, which in their nearness to the center are respectively much larger and officially count as cities, force a village-like feeling despite their size. Yet the mutation from villagers to city-inhabitants never happened in the population. Thus, the aforementioned villagers act competitively among each other and preemptively reserve their space for expansion. Does this kind of federally developed region allow for a coherent realpolitik or, with our lack of central planning, have we long ago reached the end of our spatial possibilities? One must imagine that in Switzerland the deeply rooted, decentralized structure will become a fundamental hindrance to a compact, superordinate, ecological city structure. Which generation should solve this Gordian knot?

2 Architect André Bosshard's proposal for a city in the lake addressed the area where Lake Zurich feeds into the Limmat. Published in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung in July, 1961, the ideas had very little influence on Zurich at the time.

3 Over a period of 20 years, the architect Werner Müller developed ideas to create a Lake Park in Zurich by infilling the shore in the area between Bürkliplatz and Enge. His first version, in 1956, was followed by a much-reduced version in 1974. However, when brought to the vote, it was halted as 76% of the population voted against the project. Since that time, the shoreline of Lake Zurich has become effectively untouchable.

4 In 1971, architects Guhl, Lechner, and Philipp developed a plan for creating a city within the city by covering the railroad tracks from Zurich’s Main Station to the next regional station, Altstetten. While the project was well-received by the general public, the Swiss National Railroad (SBB) was less convinced due to concerns about structural stability and feasibility.

5 HB Southwest (original name) and Eurogate (new name as of 1996) constituted the continuation of Guhl, Lechner, and Philipp’s idea for building over the tracks. While the developments from the 1990s proposed limiting the development to only cover the south-west side of the station, these projects followed the spirit of that from 1971. Under the name Europaallee, these concepts are being realized in phases that began in 2009, with planned completion in 2020.

6 Spreitenbach and Dietikon are two small cities making up part of the agglomeration of Zurich. As industrial satellite cities of Zurich, by the 1970s, they served as negative examples of urban sprawl in the Swiss Plateau. Though they began as small independent villages, they have grown to the point that they are fused together and are almost indistinguishable from one other