Peninsula

In 1881, Zurich voted to accept a project for construction of quays around Lake Zurich. This comprehensive project encompassed the entire shoreline of the city from Enge to the Zurichhorn, and became exemplary of a time of great city expansions.

Following only six years of construction, the city on the river was transformed into a city on the lake.

Zurich invested heavily in creating embankments and draining shallow areas under the leadership of Caspar Conrad Ulrich and the planning direction of the engineer Arnold Bürkli-Ziegler. These efforts allowed the successful completion of the Arboretum, the Quaibrücke, grounds along the quays of the Limmat and Lake Zurich, Seefeldquai, and the Zurichhorn. Progression of these developments along Zurich’s shores became indicators of the urban changes. This construction as well as the early-modern bathing areas along the Mythenquai, the construction of the Congress House, the parks created for the National Exhibition at the end of the 1930s, and the conversion of the Zurichhorn during the boom years at the end of the 1950s, are recognized as the “Quantum Leaps” of the shores of Lake Zurich.

This period, led by urban protagonists, was followed by a fifty-year phase of urban consolidation. The original embankments and active changing of the shoreline are today sacrosanct. In contrast, the pioneering efforts of the 19th until the mid-20th century increasingly remind one of the current revolutions in the urban fabric of Asia and the Far East, which, interestingly, are happening within similarly rapid timeframes of construction and with similar dreams for city growth. Here in Zurich, these aspirations belong to a past, no longer conceivable, time.

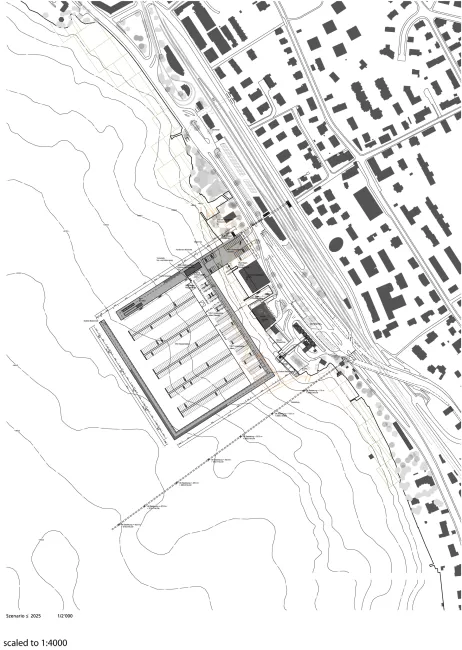

The task for a new Marina Center stipulates the coordination of the existing grounds of the city’s shores. Specifically, this is to be accomplished on the site that can be described as the “old port” for both Tiefenbrunnen and Wollishofen, two significant docks that lay vis-à-vis from each other. Here, the goal is to transform the city on the lake into a harbor city. The two prominent outposts which mark the edge of the city will mark the entrance. How does one create a concept for something like this in a time when we are afraid of architectural icons?

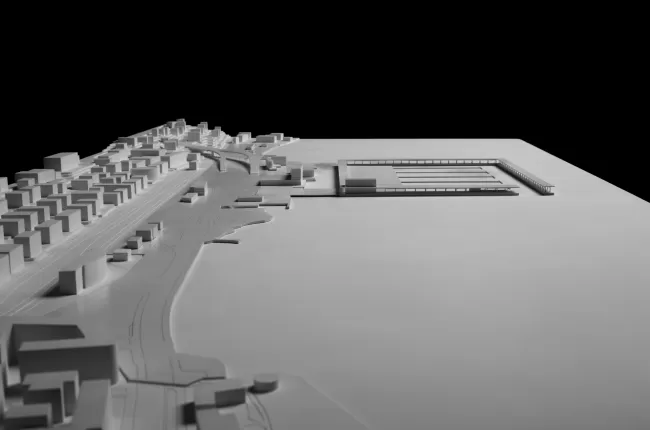

While a new cellular structure, with high buildings and water spaces, is created in Wollishofen, the marina in Tiefenbrunnen acts as a peninsula. It is anchored to the infrastructure on the land and builds a spatial relationship with the SBB property. The construction, which juts far into the lake, is not a pier, but an enclosure. As such, the harbor is covered with a floating, thin roof, just as visitors to the Utoquai were surrounded by a buoyant building as they sunbathed on the patios. The development of the site becomes an architectural endeavour and is not reduced to acting purely as infrastructure. The entire construction is accessible to the public and provides places for sitting and lying down as it steps into the water. Along the outer edges of the marina, memories of the Arteplages of the Expo 02 are reawakened. The ability of these edges to be used spontaneously creates abundant possibilities to satisfy the project’s programmatic requirements. On the side adjacent to the land and in front of the water police, the dockyard, and the diving center, one can stroll by shops while watching the sparkling white hulls of the racing boats hanging from the hand crane as they are gradually lowered into the water. In the center lies the harbor with floating steps and a dry deck for dinghies. Thin, vertically oriented wood panels allow a peek onto the dry dock where the juniors rig their boats and prepare for practice. Over the dry deck, one arrives at water spaces for the yachts. The unilateral connection mixes all forms of sailing in one location. Along the southern path, one comes to the new fitness center, a place that offers instruction to clubs, schools, and universities. Above the horizon of the roof volumes that house activities with greater space requirements rise up to four stories in height.

The lake police, professional fishermen, dockyards, divers, shops, restaurants, and bars each occupy a distinct location at the completed marina. Where the peninsula meets the land, a new park stretches from the Tiefenbrunnen train station to Zollikon, incorporating the existing infrastructure into the new design. From the Seestrasse, after passing the Tiefenbrunnen bathing facilities, one experiences a window to the lake which opens views across the water and onto the marina.

Festivals, free time activities, and climatic conditions on the shores of Lake Zurich, which bring unparalleled numbers of visitors at peak times, are quantitatively documented to cause high levels of use and interest conflicts.

The typical harbor along the shores is a threatened model. Although originally conceived with a clear differentiation between public and private property, it is only conditionally positioned to satisfy requirements for attractive public spaces.

Masterplan

In approximately 30% of the development along the shores, public access is blocked or hindered and 17% of these areas are reserved for private interests.

Peninsula

Bellerivestrasse 300

8008 Zurich

Switzerland

Landscape Architecture: Schmid Landschaftsarchitekten GmbH, Zürich

Traffic Planning: Buchhofer Barbe AG, Zurich

Model Photographs: Jon Naiman, Biel