Green Veil of Modernity

There was a time in which political buildings were supposed to be primarily symbols, built images of the society that would be invented, governed, or administered within them. Sepp Ruf’s famous Chancellor’s Bungalow, which set the scene for an elegant, open, modest Germany after 1945, was an example of this – but naturally not all political buildings became such successful symbols, a conclusion which one can see for oneself in Berlin. The SPD headquarters radiates the bleak charm of ambitiously designed document file folders, and a crane arm looms over the bow of the truncated structure as if it wished to disassemble itself; this also delivers an unintentionally fitting image of the state of the party.

The CDU headquarters at Tiergarten are just as mysterious an architectural icon: the actual building sits in a playpen of glass like a puffed-up praline, whatever that might mean. There is almost nothing to be seen architecturally from the Green Party, which is perhaps due to the history of the party itself – after all, the Green Party, and those who voted for them, consisted largely of a milieu with rather anti-modernist attitudes, who preferred to remain distant from the “inhospitable” steel-and-glass Modern Movement; this seemed to them to be the expression of a capitalistic, soulless and perfunctory lifestyle, and they reverted instead to the pinewood, granola idyll of pre-Modernism.

But the times are over in which the cool, resource-oriented technocrats with their high-speed trains, supersonic jets and other devils’ tools sat on one side, and on the other, the frightened eco’s traded their vehicles for city bicycles and business districts for community gardens.

If, of all things, one of the Green-associated foundations moves into a building that is a homage to the cool, elegant, glass-and-steel Modernist structures of the ‘60s that were so long deemed an enemy, it is perhaps the sign of a fundamental change of relationship between the environmental movement and Modernist technological enthusiasm.

With its competencies in the fields of wind and solar energy, Bluetech vehicles, and low-energy buildings, Germany is a prime example that ultramodern high-tech and the environment are not mutually exclusive – and no matter what one thinks about the architectural execution of details, the new seat of the Green-leaning Böll Foundation is a beacon for this brand of new, post-ideological eco-tech.

The competition for this 14 million Euro building was won by the young Swiss architecture office e2a. Their design revives a formalistic tradition characteristic of Mies van der Rohe, and the genetics of the Seagram Building, the Lever House, and other iconic skyscrapers of the ‘50s and ‘60s are distinctly visible in the vertical division of the aluminum-and-glass façade – only that Berlin, which is regrettable and perhaps even detrimental to the elegance of the building, did not allow it to be built nearly as tall as the architects planned.

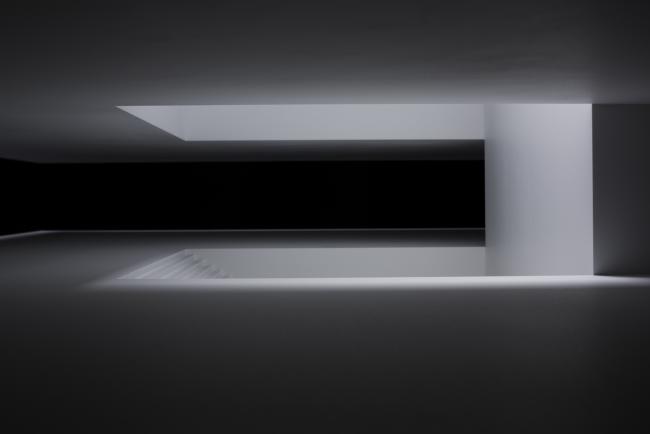

Upon entering the new building, one initially notices the vast extent of the completely glazed foyer. If events occur here at night, it will look like a small demonstration is occurring, or that a crowd is gathering underneath the structure, an effect which must naturally appeal to the operators of a political foundation.

From this public space, folded into the building’s interior, an 11 m wide stair leads up to the piano nobile, the beletage, and this stair has many functions: an amphitheater with steps for sitting, listening to lectures, watching films, or simply discussing; it is a work of art (because the jarringly green-colored runners depicting a sheep field are a unique print of the Berlin artist Via Lewandowsky); this culminates in the access to the completely green glass-enclosed piano noble, projecting over the space below, which serves as a conference center for three hundred people. One can also read this large room for sitting, discussing, and promenading as a political statement – as a place for a utopian society of discourse; architects and their clients dream of the environmental age “School of Athens” on such staircases.

It speaks to the quality of the building that it does not just send an optical green signal: the heating requirements for the space are less than half of the limit legally required by the energy conservation regulations, the roof is crowned with a photovoltaic system, and even the exhaust heat of the servers is used. The components are housed in so-called Cool-Racks, through which water flows at a temperature of 23 degrees Celsius; the servers warm this water until it reaches 30 degrees, upon which it is fed back into the heating system.

The stairs, which like a ramp pull the street life from the horizontal onto the next level, and the nonchalance of the materials, ranging from roughness to elegance in unfinished concrete, aluminum, and green and orange toned glass through whose Utopian sunglasses one can see into a more enlightened world, are evidence of the influence of Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, in whose office the 1968 and 1969 born partners Piet and Wim Eckert worked for several years. The workmanship evident in the finely punctured holes of the metal panels in the interior courtyard and the ecological detailing of the building, which will hold 185 foundation employees beginning in September, is typical of graduates of the ETH Zurich. Their Böll Foundation exhibits a construction aesthetic linked to the euphoric awakening of the young federal republic, which can be translated into architecture for everyday living in the post-fossil fuel era.

Green Veil of Modernity

Schumannstraße 8

10117 Berlin

Germany

Art on Location: Via Lewandowsky, Berlin

General Contractor: Hermann Kirchner Projektgesellschaft mbH, Bad Hersfeld

MEP: Basler & Hofmann AG, Zurich

Photographs: Jan Bitter, Berlin; Jon Naiman, Biel (Model)